Up there on the viewing platform, with heavy binoculars in hand, scanning the vast sea for elusive marine life can seem like a boring and tiresome task.

Suddenly, a spotter sees something – a dorsal fin or curved figure jumping out of the water – and everyone springs into action. The front of the boat is a coveted spot, perfect for capturing images of frisky dolphins when they start bow riding, in sync with the motion of the vessel as it glides across the water. Hours of listless searching are forgotten as excited squeals and a sense of awe fill the boat, with everyone watching the spinners and bottlenose dolphins put on a show for free in the wild.

For four days in early May, a multi-agency team led by the Department of Environment and Natural Resources and Rare crisscrossed Tañon Strait, between the islands of Cebu and Negros, to assess the status of dolphins and whales in the area. The narrow marine corridor was declared a protected seascape in 1998 because of its importance as a habitat and migratory path of marine mammals, which are facing increasing threats such as pollution and the climate crisis.

“Because they are highly migratory, large marine life are good indicators of the health of Tañon Strait. If they are still abundant, it means Tañon Strait is doing well as a marine key biodiversity area,” said Smartseas project manager Dr. Vincent Hilomen. The program co-sponsored the survey as part of efforts to improve marine protected areas in the Philippines.

In total, the team recorded and photographed six species including the intriguing Risso’s dolphins, which elicited the loudest cheers from the survey team. Like synchronized swimmers in formation, these dolphins stick their tails out of the water in a behavior known as sailing, or peer out curiously in what’s termed as spy hopping. The more energetic ones breach the surface and slam their hefty bodies back into the water in a huge belly flop. In contrast, the lone dwarf sperm whale photographed during the survey was floating serenely, with just its back and dorsal fin barely visible above the water.

New recorded dolphin subspecies

Most importantly for the survey, dwarf spinner dolphins were scientifically verified in Tañon Strait for the first time, making it a new record.

“Seeing the feisty dwarf spinner dolphins more than made up for the four LPAs (low pressure area) that cut our survey short,” lead researcher Dr. Teri Aquino wrote in a social media post. “To date, this is only the second site in the Philippines where the subspecies has been documented. The first was in 2006 in the waters surrounding Balabac island, southern Palawan by Dr. Louella Dolar’s team,” added Aquino, a wildlife veterinarian whose wide-ranging body of work also extends to crocodiles and seabirds.

Dolar has been studying dolphins and whales for almost three decades, and is acknowledged as one of the experts on these species in the Philippines. She confirmed the sighting of dwarf spinner dolphins after getting the photos from Aquino, who captured stunning images of the stubby animals as they frolicked in the waters off central Negros.

The number of dolphins and whales observed was well below previous surveys though, according to survey team leader Joe Pres Gaudiano from Rare. He had joined Dolar’s previous expeditions in Tañon Strait, and recalls seeing hundreds of dolphins with much more frequent sightings just two decades ago. This time around, sightings were few and far between, with the number of dolphins down to dozens.

The Marine Mammal Protected Areas Task Force, an experts’ group supported by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature, has named Tañon Strait an Important Marine Mammal Area (IMMA) because of the diversity of species found in the narrow channel, with 14 recorded so far, and its vital role as a foraging and resting station for dolphins and whales.

While the designation is not legally binding, it’s a scientific recognition that’s vital in policy-making, as data in IMMA sites can be compared to fisheries statistics and contribute to the crafting of regulations for ecologically sensitive areas. In the case of Tañon Strait, which faces the challenges of overfishing and increasing tourism, government agencies would benefit from greater collaboration with scientists.

Marine mammal training

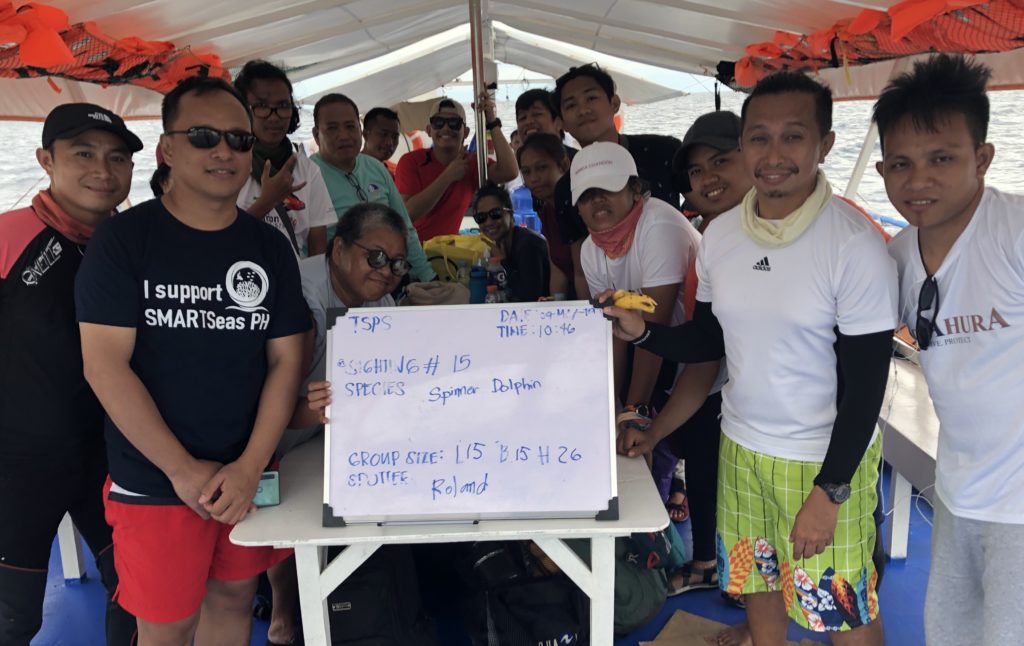

The strength of joint efforts was evident during the survey, with senior DENR officers in the region actively taking part in the rotation schedule for spotters. It’s no easy task, with four people switching posts every 30 minutes to look for dolphins and whales, followed by a rest period. Volunteers from Smartseas, the local governments of Bais and Manjuyod, and Coast Guard also joined the team in recording the sightings and marine traffic, and making sure the boat is following the transect line from a previous survey so that results can be compared. Marine mammal experts on board confirm the initial sightings from spotters, who consult a photo guide so they can practice identification skills.

On board an outrigger boat covering a distance of up to 90 kilometers per day, the team observed fishers in dugout canoes pulling squid jiggers, usually left overnight tied to a buoy. Tañon Strait abounds with several species of squid, a delicacy for Risso’s dolphins. Fish aggregating devices dotted the waters, sometimes attracting dolphins that would be spotted feeding around them.

When you’re looking for dolphins and whales, weather is the key to a productive survey. Researchers use the Beaufort scale, from force 0 (for calm waters) to force 3 (when whitecaps start to form), to decide if it’s a go. When the seas started getting choppy on the fourth day, the team had to abort the trip although everyone remained in high spirits, already planning future surveys.

Prior to the expedition, the team was required to attend an intensive classroom training and learn about the ecology of marine mammals. This is crucial for government officers that are responsible for protecting Tañon Strait, the largest marine protected area in the Philippines at around 500,000 hectares. Out of 42 local governments along the coastline, 22 are part of Rare’s Fish Forever program, which promotes responsible fishing behavior inside municipal waters.

Hands-on training was critical for the next step in the conservation of Tañon Strait: potential collaboration between the DENR’s Protected Area Office and local governments in annual monitoring surveys. Significantly, two community environment and natural resource officers from Cebu, who hold key decision-making powers, joined the survey. They took note of the telephoto lenses, GPS devices, and binoculars used so they could include proper equipment in their proposed budget for monitoring the health of marine mammals in Tañon Strait.

Hands-on training was critical for the next step in the conservation of Tañon Strait: potential collaboration between the DENR’s Protected Area Office and local governments in annual monitoring surveys. Significantly, two community environment and natural resource officers from Cebu, who hold key decision-making powers, joined the survey. They took note of the telephoto lenses, GPS devices, and binoculars used so they could include proper equipment in their proposed budget for monitoring the health of marine mammals in Tañon Strait.

“Cooperation is really needed in protecting these waters. This is good for the environment, for fishers, and also for tourism in coastal towns,” said Smartseas’ Hilomen. Everybody wins when people work together to save the whales and dolphins.