Zulma Lopez was in trouble. The past fishing season in El Porvenir, her Honduran coastal town, was plagued with bad weather, and the ten fishers who usually sold her fish, lobster, conch, and crab didn’t catch enough for her to buy and resell. When the weather was good, she could buy over 200 pounds of fish a week, earning around 2100 lempiras (~$85.90). But with sustained bad weather, her savings had dwindled, and she didn’t have the cash to purchase inventory this season. She had no product to sell and no income to pay for food, water, electricity, or her kids’ school. She had also bought product on credit to stay afloat and needed to repay the loan. Her husband, a fisher for 26 years, was barely able to bring home enough fish for them to eat.

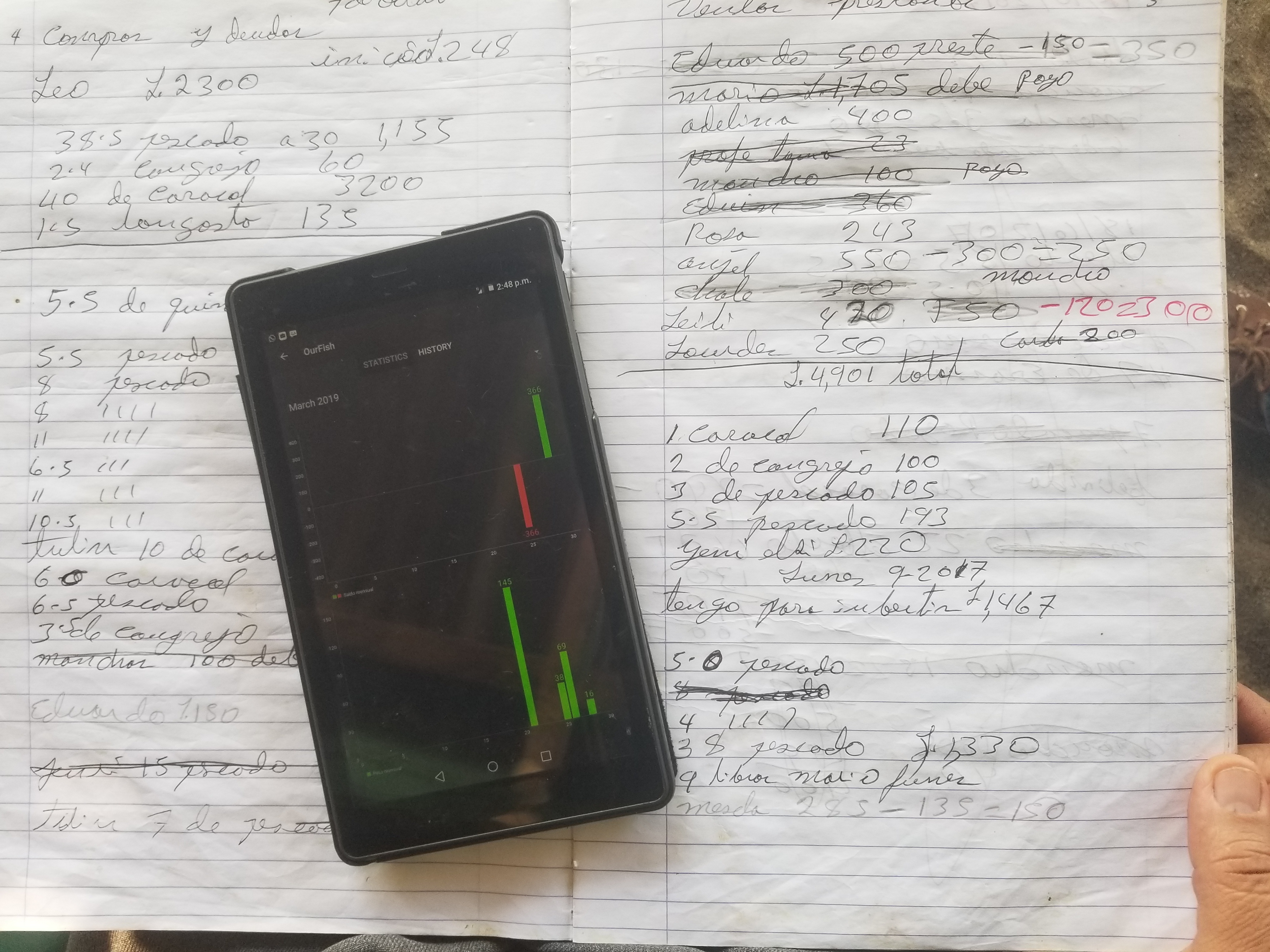

The future seemed bleak until she realized that a decision she made a year ago—to start using an app called OurFish—might provide a solution. Encouraged by Rare and its local implementing partner, the Center for Marine Studies, Zulma began using OurFish in mid-2018 to track the transactions of her fish business. Through OurFish, buyers like Zulma record their purchases with fishers, creating a permanent digital log of sales, expenses, and inventory and a log of onward sales data. The app provides transparent accounting with financial statements for fishers and buyers.

OurFish helped me keep a record of how much product I buy. It’s how I know how much I can buy a week. To help myself and to help out fishers.”

In Zulma’s case, the OurFish transaction log proved she had steady business, despite the current poor fishing season. It showed she had bought and sold over $2,500 worth of fish and seafood in the previous months before her situation changed. She realized that having the recorded digital transactions could qualify her for a formal loan from a bank.

Zulma took screenshots of her monthly transaction records along with her identification card and municipal tax ID number to the local bank, Banrural, determined to prove to the loan officer that she could repay a loan over time. After presenting her financial history, the bank granted her a $400 loan, which she’ll use to restock her product and pay down the debt to her supplier. This was the first formal loan she had ever taken out for her business, and the first time she was able to access a formal financial service from a bank.

Honduran banks require financial records to show proof of income before granting a loan, records that Zulma didn’t have, until now. “OurFish helped me keep a record of how much product I buy. It’s how I know how much I can buy a week. To help myself and to help out fishers.”

Using tools like OurFish, Fish Forever can help communities build financial and market inclusion: increasing both their access to formal financial services and the financial resilience of households. The lack of financial information for rural households has been a significant barrier to accessing financial services such as loans, savings, credit, or insurance. Instead, these communities must rely on informal and unregulated loans from money lenders (loan sharks) and the supply chain (taking product on credit or taking cash advances against future landings).

With little or no access to formal financial systems, rural homes, like Zulma and her husband’s, struggle to overcome short-term income reductions caused by bad weather or unexpected events (such as ill health), or to cover significant expenses (like repairing housing damage after a storm or replacing fishing gear). They can become trapped in a long-term poverty cycle, struggling to pay off the high-cost debt they must take on. Case in point, the interest rate on Zulma’s formal bank loan was a quarter the rate that she would normally receive from local money lenders. The financial history was critical for advancing her financial security, because having to take on more debt from local money lenders with predatory interest rates would have kept her family in a debt cycle for months to come. Fishers holding this type of debt are naturally driven to fish harder to try to repay it. Financial insecurity is, therefore, a key driver for overfishing.

OurFish helped Zulma take the first step in transitioning from the informal to the more secure, formal economy: shifting from paper records to a digital app, and from a debt relationship with a supplier to a formal loan. In Honduras, OurFish has documented over 450 tons of fish since 2017, recording transactions across 18 communities with a combined value of US$2M. Over time, the information OurFish collates will help households across the coast understand their financial situation — building profiles that can bridge the gap for financial institutions to reach the unbanked rural population.

Zulma’s is an important example of the power of giving fishing communities the tools and access to manage their lives and livelihoods. Financially resilient communities can reduce the drivers to overfish and build connections between effectively managing a business and managing the resource—the fishery—that underpins them.