Whether you’re new to behavioral science or an expert in the field, you’ve almost certainly heard about norms. There’s no doubt we all experience them: at home, at work, at school, in public places, and on the internet. Personal norms guide our individual behavior through our personal belief systems. Social norms guide individual behavior through the ways other people think and act. Even the most independent of us are affected by social norms; it’s only human to be aware of other people’s behavior and to adjust our own behavior accordingly.

But is it really that simple?

Spoiler alert: looks can be deceiving.

Cristina Bicchieri, a prominent scholar of social norms and director of the Penn Social Norms Group, says the first thing to understand about behavior as related to norms is that we have independent and interdependent behaviors. Independent behaviors include those that rely on personal needs, beliefs, and values. Interdependent behaviors rely on others’ beliefs and values. As you might expect, when thinking about social norms, we are particularly interested in the interdependent set of behaviors.

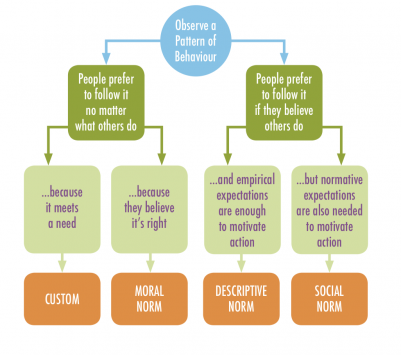

Once we’ve identified interdependent behavior, we need to determine whether it is caused by what others are doing (Bicchieri calls these empirical expectations) and/or what others think they should be doing (Bicchieri calls these normative expectations). Robert Cialdini, another social norms expert and author of Influence: The Psychology of Persuasion, labels this distinction as descriptive and injunctive norms. For example, we might determine our behavior around littering based on whether a) people around us are littering or a public place has litter (empirical/descriptive norms), and/or b) whether we’ve been told not to litter or think others believe littering is a bad behavior (normative/injunctive norms). The following flow chart from the Penn Social Norms Group helps to provide an overview of these terms.

Cialdini is also credited with a related term you may have encountered, social proof. Social proof means that you are more likely to do behavior that others similar to you (in identity, position, proximity, etc.) are doing. He further shares that we are influenced by people we find likeable and who hold positions of authority.

So, given all of this information, how do you put it into action? While personal norms are individualized, leveraging social norms means we have to attend to what people are doing as well as what they think they should be doing. We also shouldn’t forget that who does the behavior matters, especially if those people are individuals we like, have authority, or are similar to us in some way. Here’s a summary of key principles for providing social incentives for behavior change, using conservation examples:

1. Build on current, shared values and identities.

Identify common values in your target group as well as identities that could be be seen as more desirable. For example, if a group of farmers considers themselves as stewards of the environment and providers for their families, see how you can frame natural resource campaigns to align with these existing beliefs.

2. Make desired behavior visible, clear, and public.

Provide opportunities for social comparison and conversation among people. For example, if experienced and respected fishers in a community are using responsible fishing gear, highlight them as an example to motivate sustainable behavior by others who identify as a part of that group or look up to these individuals.

3. Align norms and expectations.

Make sure that your behavior change intervention creates a clear match between what people are already doing and what they feel they should be doing. If these expectations are not aligned, your campaign may backfire! For example, if you want more villagers to install rooftop solar panels, show that this is both common behavior and that it is expected by other villagers.

4. Make behavior change participatory and inclusive.

Involve your target group early on in behavior change campaigns and take the time to understand what matters to them. For example, if you’d like to encourage recycling behavior in a neighborhood, learn about whether or how this connects to people’s everyday lives and then support leaders in the community to organize behavior adoption efforts.

While norms may seem simple at first, there is a lot to understand in order to use them effectively in behavior change interventions. We hope that with these few tips, you can add norms to your toolkit of strategies for achieving conservation results.

References

Bicchieri, C. (2016). Norms in the wild: How to diagnose, measure, and change social norms. Oxford University Press.

Bicchieri, C. and Penn Social Norms Training and Consulting Group. (2015). Why people do what they do?: A social norms manual for Zimbabwe and Swaziland. Innocenti Toolkit Guide from the UNICEF Office of Research. Florence, Italy.

Butler, P., Green, K., and Galvin, D. (2013). The Principles of Pride: The science behind the mascots. Arlington, VA: Rare.

Cialdini, R. B. (2003). Crafting normative messages to protect the environment. Current directions in psychological science, 12(4), 105-109.

Cialdini, R. B. (1987). Influence (Vol. 3). Port Harcourt: A. Michel.