Paul, a Parrot, and the Power of Pride

On his first day in St. Lucia, Paul Butler hiked to the edge of the Central Forest Reserve in search of the bird that had brought him there. The brilliantly colorful, endemic St. Lucia parrot, a species at the edge of extinction, drew Paul from his native England to count the island’s remaining parrots and learn more about the species’ shrinking numbers. By 1977, the St. Lucia parrot had become a rare sight, even for the island’s locals. Studying the trees through dusk for the parrot’s distinctive lime feathers, cherry red chest and brightly burning amber eyes, Paul looked up to finally spot a single St. Lucia parrot cut a clear form against a darkening sky.

On his first day in St. Lucia, Paul Butler hiked to the edge of the Central Forest Reserve in search of the bird that had brought him there. The brilliantly colorful, endemic St. Lucia parrot, a species at the edge of extinction, drew Paul from his native England to count the island’s remaining parrots and learn more about the species’ shrinking numbers. By 1977, the St. Lucia parrot had become a rare sight, even for the island’s locals. Studying the trees through dusk for the parrot’s distinctive lime feathers, cherry red chest and brightly burning amber eyes, Paul looked up to finally spot a single St. Lucia parrot cut a clear form against a darkening sky.

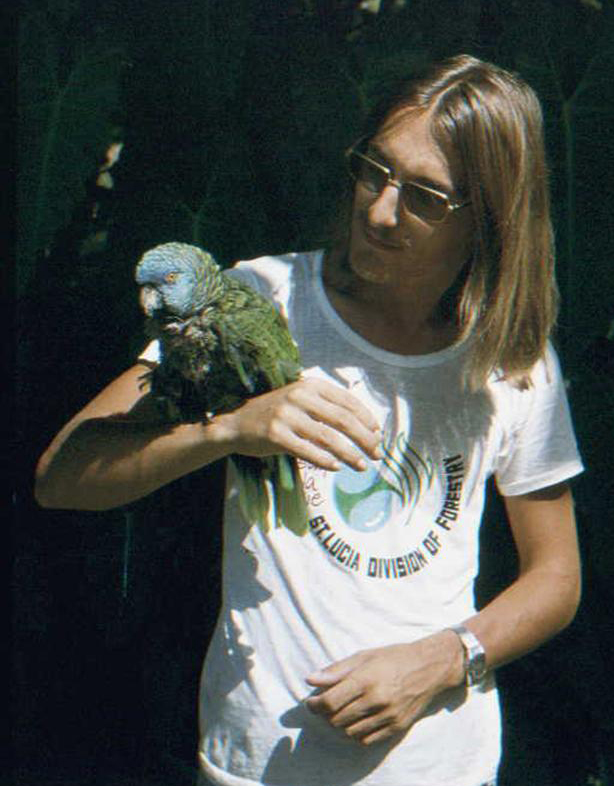

In 1977, Paul estimated that only 100 to 150 birds remained on the island. After studying the parrot’s decline, he recommended measures that St. Lucia’s forestry department could put in place to help the parrot population bounce back. The forestry department’s head made Paul an offer: Come back to St. Lucia as a conservation advisor to the forestry department, and help bring its rare bird back to the island’s forests and skies in healthy numbers. Paul accepted.

He put forth a straightforward set of solutions for protecting the St. Lucia parrot: Revise the legislation on the species (which dated back to 1885), intensify the penalty for killing the parrot (then only $5), and set up a sanctuary for the parrots within an existing forest reserve to protect their habitat.

To legalize these conservation measures and sustain them long-term, Paul knew he would need public support. In the 1970s, the birds were hunted, eaten and trapped as pets, and their habitats were increasingly destroyed by human activity. Upon spotting the bird, the average St. Lucian boy would likely pull out his slingshot and take aim. Paul and the forestry department had to figure out how to inspire St. Lucians to connect with the bird emotionally—to embrace the parrot as part of their collective identity.

When St. Lucia became independent in 1979, the government declared the St. Lucia parrot as the national bird. Paul and the forestry department used the declaration as a springboard for a public outreach program around the parrot. He and his colleagues messaged the unique value and beauty of the bird to children in classrooms across the island and through radio waves to the public through guest spots at local stations. They created a parrot mascot, Jacquot, who gave life to each of their events promoting parrot conservation. They borrowed marketing methods from the private sector and adapted them for local use, featuring the St. Lucia parrot on billboards, bumper stickers, newspaper inserts, stamps, hats, t-shirts, comics, postcards, beer mugs, key rings—and soon, the bird was everywhere.

Steadily, St. Lucia embraced the parrot as a national treasure. Between 1977 and 1988, the parrot population rebounded. Today, rather than taking aim with a slingshot, children come to the forestry department with injured parrots. On the island of St. Lucia, pride has changed the relationship between people and nature.

For years, these social marketing tools and their core purpose—tapping into the emotional side of a person’s decision-making process to change their relationship with nature—have evolved within Rare and remain central to our approach. In 1979, Rare took notice of how much St. Lucia valued its endemic parrot and asked Paul to replicate his campaign strategy to mobilize other island communities to protect their birds, starting with the St. Vincent parrot. Eventually, Paul joined Rare full-time, lending his experiences in the Caribbean to creating the Pride program and writing its first blueprint for change. Today, Rare Pride campaigns support innovative solutions for sustainable watersheds, coastal fisheries, organic agriculture, and more.